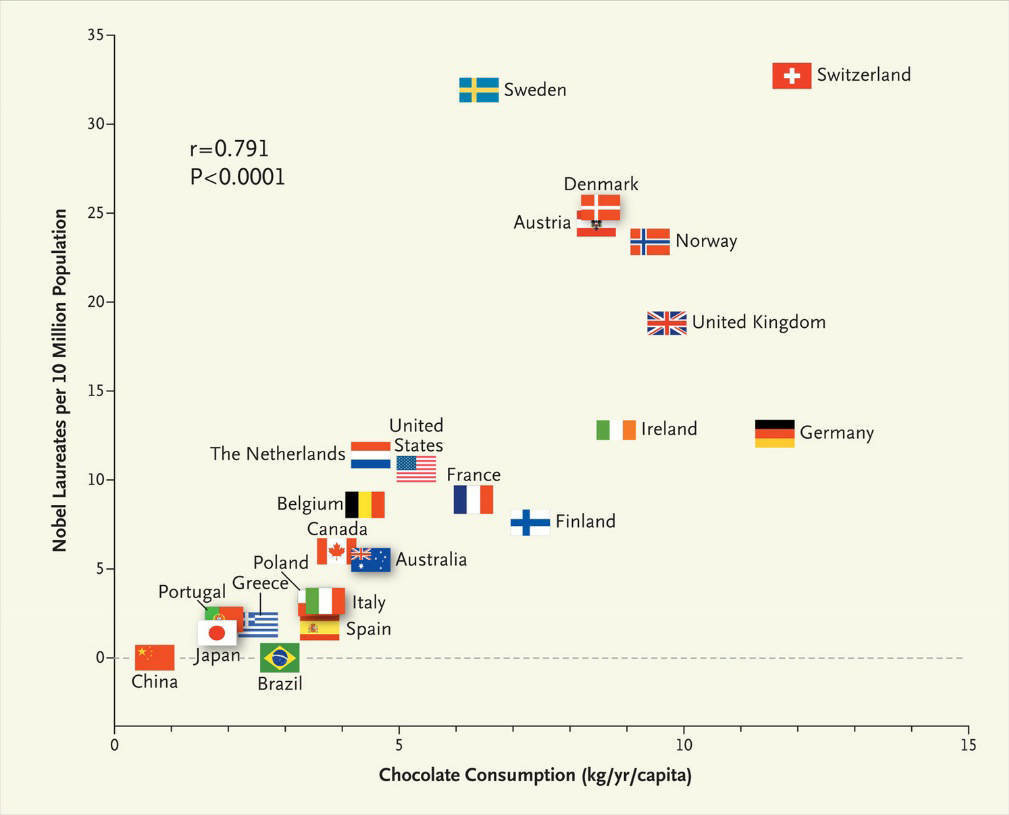

Take a look at the scatterplot below. It shows the per capita consumption of chocolate on the x axis, and the number of Nobel laureates per 10 million people on the y axis for 23 countries.

Source: Chocolate Consumption, Cognitive Function and Nobel Laureates, The New England Journal of Medecine

There is a strong correlation between chocolate consumption and the number of Nobel prizes a country has won: countries where people eat more chocolate win more Nobel prizes.

Does this mean that in order to win more Nobel prizes, governments should start implementing chocolate promotion campaigns? Of course not: eating chocolate does not make you smarter. You could also conclude from this chart that winning Nobel prizes causes the inhabitants of the the winning country to consume more chocolate. That is as nonsensical as the first explanation.

Correlation does not mean causation. When two variables are correlated, this does not necessarily mean that a change in one variable causes the change in the other one. In the case of chocolate and Nobel prizes, there is third variable at play that drives both variables on the chart: economic development.

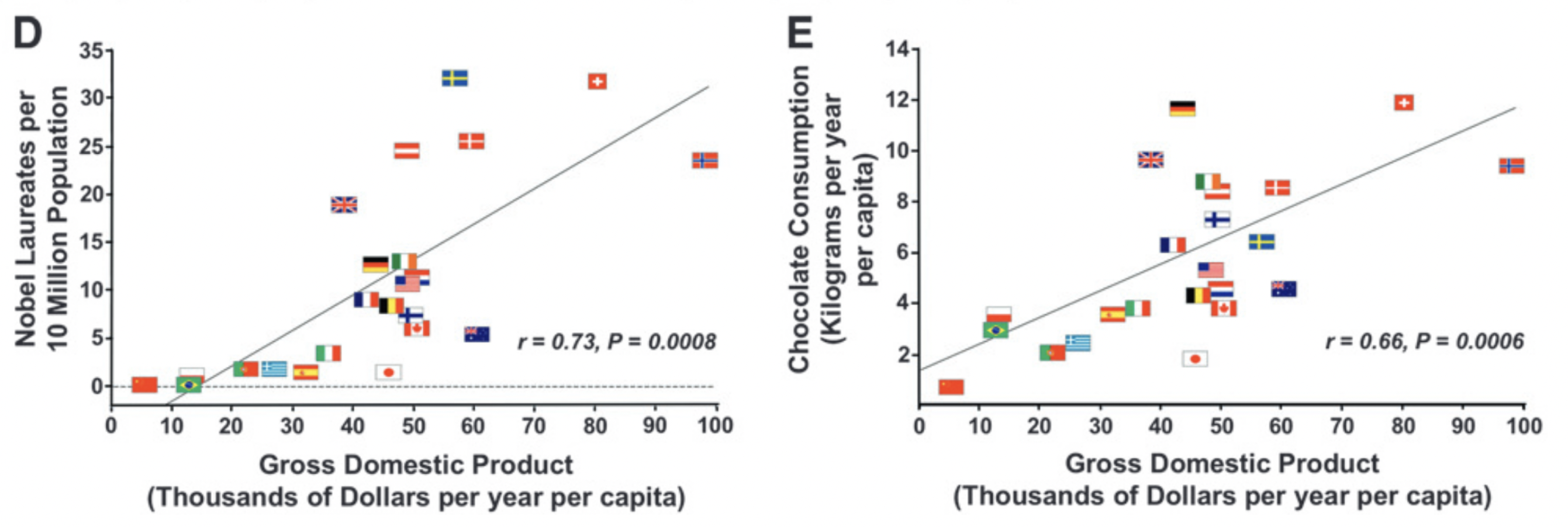

Source: Does Chocolate Consumption Really Boost Nobel Award Chances?, The Journal of Nutrition

This makes sense: when countries get richer, its inhabitants have more financial means to buy luxury goods like chocolate, and their government has more resources to invest in education, which in the long term can lead to winning more Nobel prizes.

When translating the results of scientific research into news articles, journalists often mistake correlation for causation. Here is an example of an article clearly stating that children who stay up late will become overweight teenagers.

Source: fastcompany.com

The study the article links to is Bedtime in Preschool-Aged Children and Risk for Adolescent Obesity published in The Journal of Pediatrics. This is the one sentence summary of the study:

Preschool-aged children with early weekday bedtimes were one-half as likely as children with late bedtimes to be obese as adolescents.

Moreover, in discussion of the results of the study they unequivocally state that the design of their study makes it impossible to proof causality:

Observational studies like ours cannot establish causality, and it is possible that underlying biological mechanisms drive both a child’s obesity risk and sleep requirements.

Proving causality is hard and involves randomised controlled trials. So be cautious to conclude causality from correlations.